RIPPLES IN AN ANCIENT POND

I’m crouched in a rigid bus seat, hugging my knees to my chest and shivering in my thin windbreaker as this evening high in the Peruvian Andes grows relentlessly colder and darker. Along with a handful of other Americans and our Peruvian guide, I’ve been stranded on a remote highway since mid-afternoon, waiting out the strike.

We’re some distance from the nearest town, but we aren’t alone. The narrow road is choked with nose-to-tail cars, trucks, and buses; most are old and dented, hoods held in place with bailing wire, dirty cracked windows patched with peeling duct tape. Some are tanker trucks filled with petrol, proclaiming “Pelagro!”, others are trucks with roofs mounded high with boxes and bags strapped on with rope, and there's a public passenger bus filled to capacity. All are frozen in place in front and behind us, where we ground to a halt hours ago.

Now the engines are cold and most passengers are inside like we are, trying to stay warm as we wait. I visualize them huddled in their vehicles and for a moment think we’re kindred spirits in this adventure, but on so many levels, that’s a ridiculous notion. I’m an American, different from them in ways that have nothing to do with our shared chromosomes. They’re Peruvians, and for them this isn’t an adventure, it’s a way of life they’ve known longer than any of them can remember.

We’re some distance from the nearest town, but we aren’t alone. The narrow road is choked with nose-to-tail cars, trucks, and buses; most are old and dented, hoods held in place with bailing wire, dirty cracked windows patched with peeling duct tape. Some are tanker trucks filled with petrol, proclaiming “Pelagro!”, others are trucks with roofs mounded high with boxes and bags strapped on with rope, and there's a public passenger bus filled to capacity. All are frozen in place in front and behind us, where we ground to a halt hours ago.

Now the engines are cold and most passengers are inside like we are, trying to stay warm as we wait. I visualize them huddled in their vehicles and for a moment think we’re kindred spirits in this adventure, but on so many levels, that’s a ridiculous notion. I’m an American, different from them in ways that have nothing to do with our shared chromosomes. They’re Peruvians, and for them this isn’t an adventure, it’s a way of life they’ve known longer than any of them can remember.

When I arrived in Lima two weeks ago, I was acutely aware of being in a foreign place. Unfamiliar words, smells and sights swirled around me. Smiling women with chapped mahogany faces, long ebony braids and tall brimmed hats nursed babies on rickety benches outside doors opening into the dark mysterious interiors of tiny shops. Dusty potholed streets were haphazardly lined with unpainted concrete block buildings, TV antennas and rebar bristling from their roofs. trutting roosters, thin dogs with elongated teats, and children bundled in red and purple woolen homespun mingled in an undulating tapestry of texture and color. Peru was the first South American country I'd visited, and I couldn't wait for this trip to unfold.

I joined the eleven other travelers in my group in the lobby of our hotel, where we met our Peruvian guide Alberto. He was dressed in a neat collared shirt, sweater and slacks, and spoke proudly of his country and its people. “This will

be adventures of Learning and Discovery for each of you,” he said. He would repeat those words, Learning and Discovery, many times over the next three weeks.

Albeto gave us an introduction to the ancient history of Peru, and then turned to more recent events. He described a time of terror and genocide spearheaded by a brutal guerilla group called El Sendero Luminoso, The Shining Path, which declared war on the government in 1980. During the next 20 years, over 60,000 Peruvians were killed. He shook his head and cast his eyes downward, but then told us with pride how Peru’s new president had turned everything around in only two years, ousting the terrorists and restoring order.

I joined the eleven other travelers in my group in the lobby of our hotel, where we met our Peruvian guide Alberto. He was dressed in a neat collared shirt, sweater and slacks, and spoke proudly of his country and its people. “This will

be adventures of Learning and Discovery for each of you,” he said. He would repeat those words, Learning and Discovery, many times over the next three weeks.

Albeto gave us an introduction to the ancient history of Peru, and then turned to more recent events. He described a time of terror and genocide spearheaded by a brutal guerilla group called El Sendero Luminoso, The Shining Path, which declared war on the government in 1980. During the next 20 years, over 60,000 Peruvians were killed. He shook his head and cast his eyes downward, but then told us with pride how Peru’s new president had turned everything around in only two years, ousting the terrorists and restoring order.

“It’s more safer now, because people are illegal to have guns,” he said. “Sometimes civil protests we still have against the government, but nothing like before. No.” He paused for emphasis and then said: “Nevertheless, while you are in my country here, please do not forget that you are not in America.”

How could we forget? We were there to experience the ancient and current wonders of this place, and as the gentle people we encountered welcomed us into their villages, schools and homes with warm smiles, we tried to speak their language and show them we were grateful to be there. All of us except a man from Chicago. After losing his passport at one of our hotels, he loudly and profanely accused the young woman at the front desk of stealing it; afterwards, it turned up in his pocket.

Alberto dealt with him patiently. His training included how to deal with all types of tourists, no matter how rude, and at times like this, he probably kept in mind the big tips he hoped for at the end of our trip.

On day twelve, we boarded a train that slowly labored between precipitous emerald canyon walls, on our way toward Machu Picchu. A group of doctors and nurses were on board with us, taking time off from their work for Doctors Without Borders. Most were regular visitors to Peru, and after answering our questions about their work, our conversation turned to politics.

“This so-called ‘free trade agreement’ that the U.S. is trying to force on the Peruvian government is going to wipe out thousands of small farmers in this country,” one of the doctors said. “Especially the poorest ones in rural areas that depend on agriculture for their livelihoods.”

How could we forget? We were there to experience the ancient and current wonders of this place, and as the gentle people we encountered welcomed us into their villages, schools and homes with warm smiles, we tried to speak their language and show them we were grateful to be there. All of us except a man from Chicago. After losing his passport at one of our hotels, he loudly and profanely accused the young woman at the front desk of stealing it; afterwards, it turned up in his pocket.

Alberto dealt with him patiently. His training included how to deal with all types of tourists, no matter how rude, and at times like this, he probably kept in mind the big tips he hoped for at the end of our trip.

On day twelve, we boarded a train that slowly labored between precipitous emerald canyon walls, on our way toward Machu Picchu. A group of doctors and nurses were on board with us, taking time off from their work for Doctors Without Borders. Most were regular visitors to Peru, and after answering our questions about their work, our conversation turned to politics.

“This so-called ‘free trade agreement’ that the U.S. is trying to force on the Peruvian government is going to wipe out thousands of small farmers in this country,” one of the doctors said. “Especially the poorest ones in rural areas that depend on agriculture for their livelihoods.”

“But I thought it was supposed to improve their lives!” said a woman from our group. “We were told that now they only grow enough corn or potatoes to feed themselves; wouldn’t it be better if they learned from us how to grow more productive crops?”

“Actually, no.” one of the nurses said. “It would replace the large variety of sustainable crops they grow now, with a single type of genetically engineered corn grown specifically for export to the U.S. Have you seen all the different kinds of corn they grow here?”

We nodded. Alberto had told us there were hundreds of varieties grown in Peru, and we’d seen many of them when we’d walked through open-air markets. We’d seen red, yellow, black, purple, and variegated corn. Some cobs were tiny, others as long as my forearm with kernels the size of almonds.

“Well,” the nurse continued, all that diversity will disappear, and foreign investors will be the ones who’ll benefit.”

“Not only that,” the first doctor said, “but riders on the trade agreement will prevent millions of Peruvians from access to affordable medicines. If this passes, it’ll really be bad for these people.”

“Actually, no.” one of the nurses said. “It would replace the large variety of sustainable crops they grow now, with a single type of genetically engineered corn grown specifically for export to the U.S. Have you seen all the different kinds of corn they grow here?”

We nodded. Alberto had told us there were hundreds of varieties grown in Peru, and we’d seen many of them when we’d walked through open-air markets. We’d seen red, yellow, black, purple, and variegated corn. Some cobs were tiny, others as long as my forearm with kernels the size of almonds.

“Well,” the nurse continued, all that diversity will disappear, and foreign investors will be the ones who’ll benefit.”

“Not only that,” the first doctor said, “but riders on the trade agreement will prevent millions of Peruvians from access to affordable medicines. If this passes, it’ll really be bad for these people.”

Our train finally arrived in the small town of Aguas Calientes, where we spent the night. Before dawn the next morning we boarded a bus for the trip up the steep serpentine road to Machu Picchu.

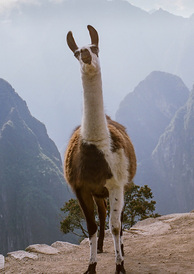

We've all seen the photos in our history books, in National Geographic, and in every travel brochure featuring trips to Peru, and for most of us, seeing this site was the reason we came. But nothing could have prepared me for the impact this place would have on me.

Thick fog shrouded the impossibly tall pinnacles that stood sentinel around this ancient and mysterious city, and as I crested a small hill on foot and saw it all spreading out before me, it literally took my breath away. No words, then or now, are adequate to describe the sensation of being in this place of wonder.

Machu Picchu is a maze of solid ruins built with blocks of stone weighing several tons each, shaped and fitted together without mortar, so tightly that not even a razor can fit between them. These structures stand in mute testimony to the skill and vision of a people who lived here over 600 years ago, and their leader Pachacuti once controlled a territory four times the size of the land conquered by Alexander the Great.

The fog lifted and divided the light of the morning sun into rays that fell on the vast expanse of stone walls, passageways and steps. I wandered in silence for hours, mist softly feathering around my shoulders. I could hear whispers of the ancients in my ears, and I realized they’d never really left this place.

We've all seen the photos in our history books, in National Geographic, and in every travel brochure featuring trips to Peru, and for most of us, seeing this site was the reason we came. But nothing could have prepared me for the impact this place would have on me.

Thick fog shrouded the impossibly tall pinnacles that stood sentinel around this ancient and mysterious city, and as I crested a small hill on foot and saw it all spreading out before me, it literally took my breath away. No words, then or now, are adequate to describe the sensation of being in this place of wonder.

Machu Picchu is a maze of solid ruins built with blocks of stone weighing several tons each, shaped and fitted together without mortar, so tightly that not even a razor can fit between them. These structures stand in mute testimony to the skill and vision of a people who lived here over 600 years ago, and their leader Pachacuti once controlled a territory four times the size of the land conquered by Alexander the Great.

The fog lifted and divided the light of the morning sun into rays that fell on the vast expanse of stone walls, passageways and steps. I wandered in silence for hours, mist softly feathering around my shoulders. I could hear whispers of the ancients in my ears, and I realized they’d never really left this place.

Back in Cuzco three days later, we loaded our bags into the storage compartment beneath our minibus, and set off for what we thought would be a seven-hour road trip. We were headed for Lake Titicaca, which straddles the border of Peru and Bolivia. At almost 13,000 feet above sea level, it’s the highest navigable lake in the world.

As we left the city, Alberto stood and told us he’d just received word on his cell phone that there was “a disturbance” on the road we were to take, which was the only road to our destination.

“This is a strike of the farm workers,” he said. “They protest a trade agreement being signed with Los Estados Unidos, the United States.”

He went on to say that strikes in Peru aren’t that unusual, even in rural areas of the country. The people who live in remote villages, some of them above 14,000 feet, are descendents of the Incas who have lived in these areas for hundreds of years. They will walk for days to assemble with townspeople in support of a common cause, and the power of their numbers can shut down the country by blocking its roads so vehicles cannot pass.

“These strikes do not last long,” Alberto said. “It gets very cold in the Andes at night, and when comes the darkness, men go back to their homes to eat and get warm. Then we clear the roads and can again drive.” He said we’d arrive at the strike area at around 5:00, so hopefully the road would be opening up by then.

We ate our lunches as we drove through the countryside on a two-lane road, passing fields being furrowed by teams of oxen and small villages with corncobs drying on every rooftop. Goats and sheep munched weeds at the side of the road; no need for herbicides here. As the sky slowly turned orange, our bus slowed and we began to crunch over rocks that became larger as we progressed.

We saw abandoned cars with their windows smashed, tree branches, broken bottles, and piles of burning tires. Some of these obstacles had been pushed to the shoulder of the road, but our driver had to weave around others. Then we noticed that no traffic was coming from the other direction, and vehicles came from behind us, driving in both lanes, inching forward, starting then stopping.

A few protestors milled along the side of the road, yelling and gesturing, but most seemed harmlessly drunk. “Borrachos,” Alberto called them. Young boys in faded t-shirts emblazoned with American logos threw rocks at us. Finally, our bus ground to a full stop. We were in a broad valley with brown treeless mountains in the distance, some topped with snow. A double line of stationary vehicles stretched out in front of us and behind as far as we could see.

A few protestors milled along the side of the road, yelling and gesturing, but most seemed harmlessly drunk. “Borrachos,” Alberto called them. Young boys in faded t-shirts emblazoned with American logos threw rocks at us. Finally, our bus ground to a full stop. We were in a broad valley with brown treeless mountains in the distance, some topped with snow. A double line of stationary vehicles stretched out in front of us and behind as far as we could see.

We were on a section of road that had no shoulder, and the ground fell away steeply on both sides. Our driver turned off the engine. It was 4:30 and there was nowhere to go. Alberto stood beside his seat at the front of the bus and faced us.

“My friends,” he said, “we are now a few miles from Cosequana, where is the hot spot of the strike. There are many rocks ahead, and we must be very patient.” Then, back in his “Learning and Discovery” mode, he added: “Here in this place we are at 11,000 feet.”

The man from Chicago squinted at his Timex Expedition watch and blurted out:

“You’re wrong! “We’re at 11,021 feet!”

“My friends,” he said, “we are now a few miles from Cosequana, where is the hot spot of the strike. There are many rocks ahead, and we must be very patient.” Then, back in his “Learning and Discovery” mode, he added: “Here in this place we are at 11,000 feet.”

The man from Chicago squinted at his Timex Expedition watch and blurted out:

“You’re wrong! “We’re at 11,021 feet!”

From my window I watched people unload belongings from their vehicles, sling them onto their backs, and walk off. Did they know this wasn’t going to be over soon? Others stood outside, leaning on their trucks and smoking. Village women walked along in the fields, babies tied across their chests and huge loads wrapped in frayed woven plastic on their backs, herding a few sheep with undocked tails. Their faces seemed to reveal acceptance of another ordinary day, month, millennium in the Andean highlands. Perhaps they knew their lives wouldn’t change, strike or no strike. There would always be hard work, inadequate medical care, corrupt politicians, and tourists stealing slices of their souls through camera lenses.

A couple of hours passed, but no one was worried yet. Someone passed around a cellophane bag of trail mix, and then a green Nalgene bottle of vodka. Happy hour in the Andes. One man said: “Wait till I tell my kids about this!” We took turns using the tiny bathroom on board, and laughed at the sign taped over the toilet that said: “Please flash twice.”

Alberto decided to walk ahead to see if he could learn any more about our situation. After about twenty minutes he arrived back at the bus, sweating and with a large bruise reddening his cheek. He mumbled something about a slingshot.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I am sorry but I must now forbid you to get off the bus,” he said. Even though our vehicle had no markings labeling it as a tourist bus carrying Americans, he said they would know. He made several calls on his cell phone, but shook his head and grimaced after each one. Men carrying sticks and open bottles of beer began to come in twos and threes down the road from town.

“Get all of you down please now!” Alberto yelled. “They must not see you!” We all dove for the floor. Soon we were surrounded by a mob of men who’d been fueling their anger and machismo for hours with cheap liquor, and their shouting and chanting grew louder. I heard the words “Los Estados Unidos” again and again, and while I couldn’t understand most of their words, their fury and defiance were unmistakable.

“Please, my friends, close tight all your windows, and pull shut the curtains,” Alberto said during a momentary lull in the chaos outside. The sun had set and it was rapidly growing dark.

One member of our group was becoming increasingly agitated. “Does the U.S. Embassy know we’re being held here against our will?” he demanded.

“Yeah, let’s nuke ‘em!” grunted Chicago.

Rocks were being thrown against the sides of our bus as we sat stiffly in the dark. I heard glass breaking, and a dull thudding of wood against metal traveling down the row of vehicles towards us. The cold walls of our bus seemed very thin, and I wished I could plug the crack where my window didn’t close all the way. I moved over into the empty seat adjacent to the aisle.

The bus began to lurch from side to side. One of our passengers, a woman from La Jolla, screamed. Her husband grabbed the seat back in front of him with one hand and threw his other arm around her, shouting: “They’re gonna push us over! Alberto, can’t you do something?” Alberto’s face was inscrutable in the blackness.

“My friends,” he intoned from the front of the bus, “I would recommend you to be very quiet, and keep your curtains closed.”

The hours passed while the uproar outside flowed and ebbed.

Now it’s after 1:00 a.m. None of us had been able to access our gear in the storage compartment under the bus, and I desperately wish I’d taken warmer clothes on board. In the dark, I search the floor and my seat back pocket for anything I might use to ward off the cold. I shake the contents from my daypack and find a map, and I unfold it and spread it over me like a blanket. I wrap my empty pack around my neck and chest, and tuck it behind me. Most of the other travelers are couples, and they’re wrapped tightly together in their seats, sharing body heat.

I glance across the narrow aisle at Chicago to find him looking at me. He illuminates his watch and hisses: “Damn! It’s 18 degrees in here!” I quickly turn toward the icy window and pretend to sleep.

Our driver periodically turns the engine on in order to operate the heater for a few minutes at a time, but the warmth quickly dissipates. Many other drivers are doing the same thing, and diesel fumes fill the air.

No one sleeps much during this endless night. A brilliant cold moon slides up from behind a mountain range in the distance, and in the spaces where the curtains don’t quite meet, I see shadowy figures weaving through this strange landscape of modern machines on a trip to nowhere across a primeval tundra.

This is the land of the ancient fertility goddess Pachamama, who’s been worshipped by the Incas and the indigenous people of the Andes for over a thousand years. She’s the Universal Mother Earth who nurtures our souls and presides over planting and harvesting. As I drift in and out of my numb stupor, I imagine her distant gaze looking down on us, and I wonder what she’s thinking.

The sun bursts into the sky like a meteor, and I’m startled into consciousness. We’re still trapped in the same place, but the protestors seem to have disappeared. For the first time in 17 hours, Alberto allows us off the bus, but tells us to stay close by. We are stiff and sore, but it’s a huge relief to stand and move our bodies. I watch a group of Peruvian women washing their hair using creek water and a bar of white soap, which they share. I can hear them talk and laugh as they comb and neatly braid their long black tresses.

Alberto decided to walk ahead to see if he could learn any more about our situation. After about twenty minutes he arrived back at the bus, sweating and with a large bruise reddening his cheek. He mumbled something about a slingshot.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I am sorry but I must now forbid you to get off the bus,” he said. Even though our vehicle had no markings labeling it as a tourist bus carrying Americans, he said they would know. He made several calls on his cell phone, but shook his head and grimaced after each one. Men carrying sticks and open bottles of beer began to come in twos and threes down the road from town.

“Get all of you down please now!” Alberto yelled. “They must not see you!” We all dove for the floor. Soon we were surrounded by a mob of men who’d been fueling their anger and machismo for hours with cheap liquor, and their shouting and chanting grew louder. I heard the words “Los Estados Unidos” again and again, and while I couldn’t understand most of their words, their fury and defiance were unmistakable.

“Please, my friends, close tight all your windows, and pull shut the curtains,” Alberto said during a momentary lull in the chaos outside. The sun had set and it was rapidly growing dark.

One member of our group was becoming increasingly agitated. “Does the U.S. Embassy know we’re being held here against our will?” he demanded.

“Yeah, let’s nuke ‘em!” grunted Chicago.

Rocks were being thrown against the sides of our bus as we sat stiffly in the dark. I heard glass breaking, and a dull thudding of wood against metal traveling down the row of vehicles towards us. The cold walls of our bus seemed very thin, and I wished I could plug the crack where my window didn’t close all the way. I moved over into the empty seat adjacent to the aisle.

The bus began to lurch from side to side. One of our passengers, a woman from La Jolla, screamed. Her husband grabbed the seat back in front of him with one hand and threw his other arm around her, shouting: “They’re gonna push us over! Alberto, can’t you do something?” Alberto’s face was inscrutable in the blackness.

“My friends,” he intoned from the front of the bus, “I would recommend you to be very quiet, and keep your curtains closed.”

The hours passed while the uproar outside flowed and ebbed.

Now it’s after 1:00 a.m. None of us had been able to access our gear in the storage compartment under the bus, and I desperately wish I’d taken warmer clothes on board. In the dark, I search the floor and my seat back pocket for anything I might use to ward off the cold. I shake the contents from my daypack and find a map, and I unfold it and spread it over me like a blanket. I wrap my empty pack around my neck and chest, and tuck it behind me. Most of the other travelers are couples, and they’re wrapped tightly together in their seats, sharing body heat.

I glance across the narrow aisle at Chicago to find him looking at me. He illuminates his watch and hisses: “Damn! It’s 18 degrees in here!” I quickly turn toward the icy window and pretend to sleep.

Our driver periodically turns the engine on in order to operate the heater for a few minutes at a time, but the warmth quickly dissipates. Many other drivers are doing the same thing, and diesel fumes fill the air.

No one sleeps much during this endless night. A brilliant cold moon slides up from behind a mountain range in the distance, and in the spaces where the curtains don’t quite meet, I see shadowy figures weaving through this strange landscape of modern machines on a trip to nowhere across a primeval tundra.

This is the land of the ancient fertility goddess Pachamama, who’s been worshipped by the Incas and the indigenous people of the Andes for over a thousand years. She’s the Universal Mother Earth who nurtures our souls and presides over planting and harvesting. As I drift in and out of my numb stupor, I imagine her distant gaze looking down on us, and I wonder what she’s thinking.

The sun bursts into the sky like a meteor, and I’m startled into consciousness. We’re still trapped in the same place, but the protestors seem to have disappeared. For the first time in 17 hours, Alberto allows us off the bus, but tells us to stay close by. We are stiff and sore, but it’s a huge relief to stand and move our bodies. I watch a group of Peruvian women washing their hair using creek water and a bar of white soap, which they share. I can hear them talk and laugh as they comb and neatly braid their long black tresses.

Alberto decides to walk ahead to see if he can figure out what our options are, and after about two hours, returns with another driver who has a bus safely parked about five miles ahead, on the other side of Cosequana. He says the rioting is starting up again there, but if we could perhaps walk around the outskirts of the town, we might be able to get to his bus, and he thought the road was open from there on to our destination.

We unload our luggage from the belly of the bus, but a problem quickly surfaces. Several in the group are unable to carry their own luggage. Alberto disappears again and returns with three villagers and their “taxi-cholos:” tricycles built with two wheels on the front and a seat where passengers can sit while the driver pedals from behind. Now they’re going to be used to carry large suitcases, each of which probably contains more clothes than any of these taxi-cholo men have ever owned.

We begin to walk up the road between the vehicles. We’re all exhausted, hungry and dehydrated, but we press on and after a couple of miles come to the main road blockage: rocks half as big as cars, cement lampposts laying on their sides, and felled trees. I’m pulling my wheeled duffle, but when I arrive at these obstacles, I have to stop and climb over, hauling it with me. We leave the stranded vehicles behind, and continue down the empty road. We pass a few Peruvians as we walk, but keep our heads down and try to act invisible.

We come to a squat, solid concrete building painted pink and magenta. On the front are the words “National Policia de Peru.” Alberto talks with the uniformed guard at the entry, and then we’re given permission to enter the courtyard, where we collapse on the ground against a wall. Several police are lounging in the courtyard, and look at us curiously. They are young and strikingly handsome with their classic Peruvian profiles and perfectly pressed olive uniforms.

Alberto goes inside the station and remains there quite awhile before emerging. He walks over to where we’re assembled, and he’s acting fidgety. He says the chief of police told him the civil unrest is continuing unabated in the town center, and the police have deliberately stayed away for fear of fanning the flames and making things worse. “The people are very angry,” he says. “They are angry against the United States and they are angry against their own government.”

He tells us he’s asked the chief to provide an armed escort for us around the perimeter of the town, well away from the demonstration, but the chief is reluctant. Alberto paces the courtyard for a few minutes, then leaves and returns carrying two cases of Inca Kola, and disappears again into the office. After several minutes, he emerges and nods to us.

We unload our luggage from the belly of the bus, but a problem quickly surfaces. Several in the group are unable to carry their own luggage. Alberto disappears again and returns with three villagers and their “taxi-cholos:” tricycles built with two wheels on the front and a seat where passengers can sit while the driver pedals from behind. Now they’re going to be used to carry large suitcases, each of which probably contains more clothes than any of these taxi-cholo men have ever owned.

We begin to walk up the road between the vehicles. We’re all exhausted, hungry and dehydrated, but we press on and after a couple of miles come to the main road blockage: rocks half as big as cars, cement lampposts laying on their sides, and felled trees. I’m pulling my wheeled duffle, but when I arrive at these obstacles, I have to stop and climb over, hauling it with me. We leave the stranded vehicles behind, and continue down the empty road. We pass a few Peruvians as we walk, but keep our heads down and try to act invisible.

We come to a squat, solid concrete building painted pink and magenta. On the front are the words “National Policia de Peru.” Alberto talks with the uniformed guard at the entry, and then we’re given permission to enter the courtyard, where we collapse on the ground against a wall. Several police are lounging in the courtyard, and look at us curiously. They are young and strikingly handsome with their classic Peruvian profiles and perfectly pressed olive uniforms.

Alberto goes inside the station and remains there quite awhile before emerging. He walks over to where we’re assembled, and he’s acting fidgety. He says the chief of police told him the civil unrest is continuing unabated in the town center, and the police have deliberately stayed away for fear of fanning the flames and making things worse. “The people are very angry,” he says. “They are angry against the United States and they are angry against their own government.”

He tells us he’s asked the chief to provide an armed escort for us around the perimeter of the town, well away from the demonstration, but the chief is reluctant. Alberto paces the courtyard for a few minutes, then leaves and returns carrying two cases of Inca Kola, and disappears again into the office. After several minutes, he emerges and nods to us.

We leave the police station in a tight group with four armed policemen in front, two along the sides, and four bringing up the rear. We stay close together and silent. We’re led on a circuitous route alongside fields and across rickety bridges over creeks where women washing clothes look up at us in surprise. We pass a man herding three bony cows along a path. We walk and walk, then come to the outskirts of Cosequana and continue onto its back streets.

Buildings are now on both sides of us, and at every intersection, the lead policemen pause and look down the cross streets with their hands on their guns before they let us pass. We can hear yelling in the distance, and I envision a mob charging at us from a side street brandishing sticks and stones, but it doesn’t happen. Instead, children run towards us giggling, calling out “Hola Senora!” A tantalizing aroma of cooking meat, spices and chilies wafts from a streetside food vendor. Curious eyes peer at us from doorways, little girls in a courtyard are practicing a dance, laundry flaps on a rooftop, and chickens peck.

Finally we reach the gated parking lot where the small bus is waiting. We tip the police officers and the taxi cholo drivers who arrive with our luggage, thank them with many “Muchas Graciases” and climb aboard. There are bottles of water. The bus turns out onto the street and heads north.

* * *

It’s my last day in Peru, and I have some time to walk the streets of Lima on my own before heading to the airport for a late-night departure. I enter a shop called “The Center for Traditional Textiles,” and I admire the many beautiful woolen weavings stacked in piles on the floor. A woman in the back sits at a large loom, sending the shuttlecock back and forth, click clack. The nicely dressed salesman isn’t pushy, and lets me browse. Only when I closely examine the intricate patterns on a multicolored blanket does he come forward.

“All the designs you see have special meaning for us,” he says. “See these stripes? They stand for furrows, because we believe that you reap what you sow.”

I point to a pattern that is repeated countless times, shaped like an expanding asterisk.

“Ah,” he says, smoothing the fabric gently. “Do you know how it looks when you drop a pebble into a pond?” I nod.

“I think you Americans call it a ‘ripple effect.’ We believe every action we take has a continuing effect on many other things. And sometimes,” he says, “we are too busy looking at the pebble to see the ripples.”

Buildings are now on both sides of us, and at every intersection, the lead policemen pause and look down the cross streets with their hands on their guns before they let us pass. We can hear yelling in the distance, and I envision a mob charging at us from a side street brandishing sticks and stones, but it doesn’t happen. Instead, children run towards us giggling, calling out “Hola Senora!” A tantalizing aroma of cooking meat, spices and chilies wafts from a streetside food vendor. Curious eyes peer at us from doorways, little girls in a courtyard are practicing a dance, laundry flaps on a rooftop, and chickens peck.

Finally we reach the gated parking lot where the small bus is waiting. We tip the police officers and the taxi cholo drivers who arrive with our luggage, thank them with many “Muchas Graciases” and climb aboard. There are bottles of water. The bus turns out onto the street and heads north.

* * *

It’s my last day in Peru, and I have some time to walk the streets of Lima on my own before heading to the airport for a late-night departure. I enter a shop called “The Center for Traditional Textiles,” and I admire the many beautiful woolen weavings stacked in piles on the floor. A woman in the back sits at a large loom, sending the shuttlecock back and forth, click clack. The nicely dressed salesman isn’t pushy, and lets me browse. Only when I closely examine the intricate patterns on a multicolored blanket does he come forward.

“All the designs you see have special meaning for us,” he says. “See these stripes? They stand for furrows, because we believe that you reap what you sow.”

I point to a pattern that is repeated countless times, shaped like an expanding asterisk.

“Ah,” he says, smoothing the fabric gently. “Do you know how it looks when you drop a pebble into a pond?” I nod.

“I think you Americans call it a ‘ripple effect.’ We believe every action we take has a continuing effect on many other things. And sometimes,” he says, “we are too busy looking at the pebble to see the ripples.”